Was The 17th Amendment Successful

The Seventeenth Amendment (Amendment XVII) to the United states Constitution established the direct election of United States senators in each state. The amendment supersedes Commodity I, Department 3, Clauses i andii of the Constitution, nether which senators were elected by state legislatures. Information technology also alters the procedure for filling vacancies in the Senate, assuasive for state legislatures to permit their governors to make temporary appointments until a special election can be held.

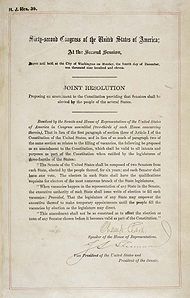

The subpoena was proposed by the 62nd Congress in 1912 and became part of the Constitution on April 8, 1913, on ratification by three-quarters (36) of the state legislatures. Sitting senators were not affected until their existing terms expired. The transition began with two special elections in Georgia[1] and Maryland, and so in earnest with the November 1914 election; information technology was complete on March 4, 1919, when the senators chosen at the November 1918 election took office.

Text [edit]

The Senate of the The states shall exist composed of two Senators from each Land, elected by the people thereof, for six years; and each Senator shall have ane vote. The electors in each Land shall take the qualifications requisite for electors of the well-nigh numerous co-operative of the State legislatures.

When vacancies happen in the representation of any State in the Senate, the executive authority of such State shall issue writs of election to fill such vacancies: Provided, That the legislature of whatever State may empower the executive thereof to make temporary appointments until the people fill the vacancies by election as the legislature may direct.

This amendment shall not be so construed as to affect the ballot or term of whatsoever Senator chosen before it becomes valid as office of the Constitution.[2]

Background [edit]

Original composition [edit]

Originally, under Article I, Section 3, Clauses 1 and2 of the Constitution, each land legislature elected its state's senators for a six-year term.[3] Each state, regardless of size, is entitled to two senators equally part of the Connecticut Compromise between the small and large states.[4] This contrasted with the Firm of Representatives, a body elected by pop vote, and was described as an uncontroversial decision; at the time, James Wilson was the sole advocate of popularly electing the Senate, but his proposal was defeated 10–1.[5] There were many advantages to the original method of electing senators. Prior to the Constitution, a federal trunk was ane where states finer formed cypher more than permanent treaties, with citizens retaining their loyalty to their original state. However, nether the new Constitution, the federal government was granted substantially more than ability than before. Having the state legislatures elect the senators reassured anti-federalists that there would be some protection confronting the federal authorities's swallowing up states and their powers,[6] and providing a check on the power of the federal government.[7]

Additionally, the longer terms and abstention of popular election turned the Senate into a body that could counter the populism of the Business firm. While the representatives operated in a two-twelvemonth direct election cycle, making them frequently accountable to their constituents, the senators could afford to "have a more detached view of issues coming before Congress".[8] State legislatures retained the theoretical correct to "instruct" their senators to vote for or against proposals, thus giving the states both direct and indirect representation in the federal government.[9] The Senate was part of a formal bicameralism, with the members of the Senate and House responsible to completely distinct constituencies; this helped defeat the problem of the federal government existence subject to "special interests".[10] Members of the Constitutional Convention considered the Senate to be parallel to the British Business firm of Lords as an "upper business firm", containing the "better men" of guild, merely improved upon as they would be conscientiously called past the upper houses of state legislatures for fixed terms, and not simply inherited for life every bit in the British system, subject field to a monarch's arbitrary expansion. Information technology was hoped they would provide abler deliberation and greater stability than the Business firm of Representatives due to the senators' status.[11]

Issues [edit]

According to Estimate Jay Bybee of the Us Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit, those in favor of popular elections for senators believed 2 primary issues were caused by the original provisions: legislative corruption and electoral deadlocks.[12] There was a sense that senatorial elections were "bought and sold", irresolute hands for favors and sums of money rather than because of the competence of the candidate. Between 1857 and 1900, the Senate investigated three elections over abuse. In 1900, for case, William A. Clark had his election voided later the Senate concluded that he had bought votes in the Montana legislature. Simply bourgeois analysts Bybee and Todd Zywicki believe this business was largely unfounded; at that place was a "dearth of difficult information" on the field of study.[13] In more than than a century of legislative elections of U.S. senators, only ten cases were contested for allegations of venial.[xiv]

Electoral deadlocks were some other upshot. Because country legislatures were charged with deciding whom to appoint as senators, the system relied on their power to agree. Some states could not, and thus delayed sending senators to Congress; in a few cases, the arrangement broke down to the point where states completely lacked representation in the Senate.[15] Deadlocks started to become an issue in the 1850s, with a deadlocked Indiana legislature allowing a Senate seat to sit vacant for 2 years.[16] The tipping signal came in 1865 with the election of John P. Stockton (D-NJ), which happened later on the New Jersey legislature changed its rules regarding the definition of a quorum and was thus elected by plurality instead of by absolute majority.[17]

In 1866, Congress acted to standardize a two-step process for Senate elections.[eighteen] In the first step, each chamber of the country legislature would meet separately to vote. The following solar day, the chambers would meet in "joint assembly" to appraise the results, and if a bulk in both chambers had voted for the same person, he would be elected. If not, the joint associates would vote for a senator, with each member receiving a vote. If no person received a bulk, the articulation assembly was required to keep convening every 24-hour interval to take at least ane vote until a senator was elected.[nineteen] However, between 1891 and 1905, 46 elections were deadlocked across 20 states;[14] in one farthermost case, a Senate seat for Delaware went unfilled from 1899 until 1903.[20] The business of belongings elections besides acquired great disruption in the state legislatures, with a full tertiary of the Oregon House of Representatives choosing not to swear the oath of part in 1897 due to a dispute over an open Senate seat. The result was that Oregon's legislature was unable to pass legislation that yr.[20]

Zywicki again argues that this was not a serious issue. Deadlocks were a problem, but they were the exception rather than the norm; many legislatures did non deadlock over elections at all. Most of those that did in the 19th century were the newly admitted western states, which suffered from "inexperienced legislatures and weak party field of study... as western legislatures gained experience, deadlocks became less frequent." While Utah suffered from deadlocks in 1897 and 1899, they became what Zywicki refers to every bit "a good instruction experience", and Utah never over again failed to elect senators.[21] Another concern was that when deadlocks occurred, land legislatures were unable to conduct their other normal business; James Christian Ure, writing in the S Texas Law Review, notes that this did not in fact occur. In a deadlock state of affairs, country legislatures would bargain with the thing by holding "i vote at the beginning of the twenty-four hour period—so the legislators would continue with their normal affairs".[22]

Eventually, legislative elections held in a state's Senate ballot years were perceived to have go so dominated by the business organisation of picking senators that the state's choice for senator distracted the electorate from all other pertinent issues.[23] Senator John H. Mitchell noted that the Senate became the "vital upshot" in all legislative campaigns, with the policy stances and qualifications of state legislative candidates ignored by voters who were more interested in the indirect Senate election.[24] To remedy this, some land legislatures created "informational elections" that served as de facto general elections, allowing legislative campaigns to focus on local issues.[24]

Calls for reform [edit]

Calls for a constitutional amendment regarding Senate elections started in the early 19th century, with Henry R. Storrs in 1826 proposing an amendment to provide for popular ballot.[25] Similar amendments were introduced in 1829 and 1855, with the "virtually prominent" proponent being Andrew Johnson, who raised the result in 1868 and considered the thought's claim "and so palpable" that no additional explanation was necessary.[26] As noted to a higher place, in the 1860s, there was a major congressional dispute over the issue, with the House and Senate voting to veto the engagement of John P. Stockton to the Senate due to his approval by a plurality of the New Bailiwick of jersey Legislature rather than a majority. In reaction, the Congress passed a bill in July 1866 that required state legislatures to elect senators by an accented majority.[26]

By the 1890s, support for the introduction of direct election for the Senate had essentially increased, and reformers worked on 2 fronts. On the commencement forepart, the Populist Political party incorporated the directly ballot of senators into its Omaha Platform, adopted in 1892.[27] In 1908, Oregon passed the offset law basing the selection of U.S. senators on a pop vote. Oregon was soon followed by Nebraska.[28] Proponents for popular election noted that ten states already had non-binding primaries for Senate candidates,[29] in which the candidates would be voted on past the public, effectively serving as informational referendums instructing state legislatures how to vote;[29] reformers campaigned for more states to introduce a like method.

William Randolph Hearst opened a nationwide pop readership for direct election of U.Southward. senators in a 1906 series of articles using flamboyant language attacking "The Treason of the Senate" in his Cosmopolitan magazine. David Graham Philips, 1 of the "yellow journalists" whom President Teddy Roosevelt called "muckrakers", described Nelson Aldrich of Rhode Island as the chief "traitor" amidst the "scurvy lot" in control of the Senate by theft, perjury, and bribes corrupting the state legislatures to gain election to the Senate. A few state legislatures began to petition the Congress for direct election of senators. By 1893, the Business firm had the two-thirds vote for just such an amendment. However, when the articulation resolution reached the Senate, it failed from fail, as information technology did again in 1900, 1904 and 1908; each time the Business firm approved the appropriate resolution, and each time it died in the Senate.[30]

On the second national legislative front, reformers worked toward a constitutional subpoena, which was strongly supported in the Business firm of Representatives but initially opposed by the Senate. Bybee notes that the country legislatures, which would lose power if the reforms went through, were supportive of the campaign. By 1910, 31 country legislatures had passed resolutions calling for a constitutional subpoena allowing direct election, and in the same year x Republican senators who were opposed to reform were forced out of their seats, interim as a "wake-up telephone call to the Senate".[29]

Reformers included William Jennings Bryan, while opponents counted respected figures such as Elihu Root and George Frisbie Hoar amid their number; Root cared and then strongly most the effect that later on the passage of the Seventeenth Amendment he refused to stand up for re‑election to the Senate.[12] Bryan and the reformers argued for popular election through highlighting flaws they saw within the existing organisation, specifically corruption and balloter deadlocks, and through arousing populist sentiment. Most important was the populist argument; that there was a need to "Awaken, in the senators... a more than acute sense of responsibleness to the people", which information technology was felt they lacked; election through state legislatures was seen as an anachronism that was out of step with the wishes of the American people, and i that had led to the Senate condign "a sort of aristocratic body—likewise far removed from the people, across their reach, and with no special interest in their welfare".[31] The settlement of the West and continuing assimilation of hundreds of thousands of immigrants expanded the sense of "the people".

Hoar replied that "the people" were both a less permanent and a less trusted body than state legislatures, and moving the responsibleness for the election of senators to them would run into it passing into the hands of a torso that "[lasted] merely a day" before changing. Other counterarguments were that renowned senators could non have been elected directly and that, since a large number of senators had experience in the House (which was already directly elected), a constitutional amendment would be pointless.[32] The reform was considered by opponents to threaten the rights and independence of u.s., who were "sovereign, entitled... to accept a dissever branch of Congress... to which they could send their ambassadors." This was countered by the argument that a modify in the style in which senators were elected would not change their responsibilities.[33]

The Senate freshman class of 1910 brought new hope to the reformers. 14 of the xxx newly elected senators had been elected through party primaries, which amounted to popular choice in their states. More than half of the states had some course of principal choice for the Senate. The Senate finally joined the House to submit the Seventeenth Amendment to the states for ratification, nearly ninety years after it starting time was presented to the Senate in 1826.[34]

By 1912, 239 political parties at both the land and national level had pledged some form of direct election, and 33 states had introduced the use of directly primaries.[35] Xx-vii states had called for a ramble convention on the subject, with 31 states needed to attain the threshold; Arizona and New Mexico each achieved statehood that year (bringing the total number of states to 48), and were expected to back up the movement. Alabama and Wyoming, already states, had passed resolutions in favor of a convention without formally calling for one.[36]

Proposal and ratification [edit]

Proposal in Congress [edit]

In 1911, the Business firm of Representatives passed House Joint Resolution 39 proposing a constitutional subpoena for straight election of senators. The original resolution passed by the House contained the following clause:[37]

The times, places, and manner of holding elections for Senators shall be as prescribed in each State past the legislature thereof.

This so-called "race passenger" clause would accept strengthened the powers of states over senatorial elections and weakened those of Congress past overriding Congress'south ability to override state laws affecting the way of senatorial elections.[38]

Since the plough of the century, almost blacks in the South, and many poor whites, had been disenfranchised by country legislatures passing constitutions with provisions that were discriminatory in do. This meant that their millions of population had no political representation. Most of the South had one-party states. When the resolution came before the Senate, a substitute resolution, ane without the rider, was proposed past Joseph L. Bristow of Kansas. Information technology was adopted by a vote of 64 to 24, with four non voting.[39] Almost a twelvemonth later, the Business firm accepted the change. The conference study that would become the Seventeenth Amendment was approved by the Senate 42 to 36 on Apr 12, 1912, and by the House 238 to 39, with 110 not voting on May xiii, 1912.

Ratification by the states [edit]

Original ratifier of amendment

Ratified after adoption

Rejected amendment

No activity taken on amendment

Having been passed by Congress, the amendment was sent to the states for ratification and was ratified by:[twoscore]

- Massachusetts: May 22, 1912

- Arizona: June 3, 1912

- Minnesota: June 10, 1912

- New York: January 15, 1913

- Kansas: Jan 17, 1913

- Oregon: January 23, 1913

- North Carolina: Jan 25, 1913

- California: January 28, 1913

- Michigan: January 28, 1913

- Iowa: January 30, 1913

- Montana: January 30, 1913

- Idaho: January 31, 1913

- West Virginia: Feb 4, 1913

- Colorado: February five, 1913

- Nevada: Feb 6, 1913

- Texas: Feb 7, 1913

- Washington: Feb 7, 1913

- Wyoming: Feb 8, 1913

- Arkansas: Feb 11, 1913

- Maine: February 11, 1913

- Illinois: February 13, 1913

- North Dakota: February 14, 1913

- Wisconsin: February 18, 1913

- Indiana: February 19, 1913

- New Hampshire: February xix, 1913

- Vermont: Feb 19, 1913

- South Dakota: February 19, 1913

- Oklahoma: February 24, 1913

- Ohio: February 25, 1913

- Missouri: March 7, 1913

- New Mexico: March xiii, 1913

- Nebraska: March 14, 1913

- New Bailiwick of jersey: March 17, 1913

- Tennessee: April 1, 1913

- Pennsylvania: April two, 1913

- Connecticut: Apr 8, 1913

With 36 states having ratified the Seventeenth Amendment, it was certified by Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan on May 31, 1913, as office of the Constitution.[40] The amendment has subsequently been ratified by: - Louisiana: June 11, 1914

- Alabama: April 11, 2002[41]

- Delaware: July ane, 2010[42] (after rejecting the amendment on March 18, 1913)

- Maryland: April 1, 2012[43] [44] [45]

- Rhode Island: June 20, 2014

The Utah legislature rejected the subpoena on February 26, 1913. No activeness on the amendment has been completed by Florida,[46] Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, South Carolina, Virginia, Alaska or Hawaii. Alaska and Hawaii were not nonetheless states at the time of the amendment's proposal, and have never taken whatsoever official action to support or oppose the amendment since achieving statehood.

Effect [edit]

Most importantly, the Seventeenth Amendment removed state government representation from the legislative arm of the federal government. Originally, the people themselves did not elect senators; instead, states appointed senators. The senators represented u.s.a.' interests, while the House of Representatives represented the interests of the people.

The Seventeenth Amendment altered the process for electing Usa senators and changed the way vacancies would exist filled. Originally, the Constitution required state legislatures to fill Senate vacancies.

According to Judge Bybee, the Seventeenth Amendment had a dramatic impact on the political composition of the U.S. Senate.[47] Earlier the Supreme Courtroom required "ane man, i vote" in Reynolds v. Sims (1964), malapportionment of state legislatures was common. For example, rural counties and cities could be given "equal weight" in the state legislatures, enabling one rural vote to equal 200 metropolis votes. The malapportioned state legislatures would have given the Republicans control of the Senate in the 1916 Senate elections. With straight ballot, each vote represented equally, and the Democrats retained command of the Senate.[48]

The reputation of corrupt and arbitrary state legislatures connected to decline as the Senate joined the Firm of Representatives implementing popular reforms. Bybee has argued that the amendment led to complete "discredit" for state legislatures without the buttress of a land-based check on Congress. In the decades post-obit the Seventeenth Subpoena, the federal government was enabled to enact progressive measures.[49] However, Schleiches argues that the separation of land legislatures and the Senate had a beneficial result on u.s.a., as it led state legislative campaigns to focus on local rather than national issues.[24]

New Deal legislation is another example of expanding federal regulation overruling the land legislatures promoting their local land interests in coal, oil, corn and cotton fiber.[50] Ure agrees, saying that not but is each senator at present free to ignore his state's interests, senators "have incentive to use their advice-and-consent powers to install Supreme Court justices who are inclined to increase federal power at the expense of state sovereignty".[51] Over the first half of the 20th century, with a popularly elected Senate confirming nominations, both Republican and Democratic, the Supreme Court began to apply the Beak of Rights to the states, overturning country laws whenever they harmed individual state citizens.[52] It aimed to limit the influence of the wealthy.[53]

Filling vacancies [edit]

The Seventeenth Amendment requires a governor to call a special election to fill vacancies in the Senate.[54] It also allows a state'southward legislature to permit its governor to brand temporary appointments, which concluding until a special election is held to fill the vacancy. Currently, all but 5 states (N Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin) let such appointments.[55] The Constitution does not set out how the temporary appointee is to be selected.

First direct elections to the Senate [edit]

Oklahoma, admitted to statehood in 1907, chose a senator past legislative election 3 times: twice in 1907, when admitted, and once in 1908. In 1912, Oklahoma reelected Robert Owen by advisory popular vote.[56]

Oregon held primaries in 1908 in which the parties would run candidates for that position, and the country legislature pledged to choose the winner as the new senator.[57]

New Mexico, admitted to statehood in 1912, chose only its first two senators legislatively. Arizona, admitted to statehood in 1912, chose its first two senators past advisory pop vote. Alaska, and Hawaii, admitted to statehood in 1959, have never called a U.Southward. senator legislatively.[56]

The first election subject field to the Seventeenth Amendment was a tardily ballot in Georgia held June xv, 1913. Augustus Octavius Bacon was even so unopposed.

The first direct elections to the Senate following the Seventeenth Amendment being adopted were:[56]

- In Maryland on Nov 4, 1913: a grade 1 special election due to a vacancy, for a term ending in 1917.

- In Alabama on May eleven, 1914: a class three special ballot due to a vacancy, for a term ending in 1915.

- Nationwide in 1914: All 32 form 3 senators, term 1915–1921

- Nationwide in 1916: All 32 class 1 senators, term 1917–1923

- Nationwide in 1918: All 32 class 2 senators, term 1919–1925

Court cases and interpretation controversies [edit]

In Trinsey v. Pennsylvania (1991),[58] the United States Courtroom of Appeals for the Third Circuit was faced with a state of affairs where, following the death of Senator John Heinz of Pennsylvania, Governor Bob Casey had provided for a replacement and for a special ballot that did non include a primary.[59] A voter and prospective candidate, John S. Trinsey Jr., argued that the lack of a master violated the Seventeenth Amendment and his right to vote under the Fourteenth Amendment.[60] The Third Circuit rejected these arguments, ruling that the Seventeenth Amendment does non require primaries.[61]

Another subject of assay is whether statutes restricting the say-so of governors to appoint temporary replacements are constitutional. Vikram Amar, writing in the Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly, claims Wyoming's requirement that its governor fill a senatorial vacancy by nominating a person of the same party as the person who vacated that seat violates the Seventeenth Subpoena.[62] This is based on the text of the Seventeenth Subpoena, which states that "the legislature of any state may empower the executive thereof to make temporary appointments". The amendment merely empowers the legislature to consul the authority to the governor and, once that authorisation has been delegated, does not permit the legislature to arbitrate. The authority is to determine whether the governor shall take the power to appoint temporary senators, non whom the governor may engage.[63] Sanford Levinson, in his rebuttal to Amar, argues that rather than engaging in a textual interpretation, those examining the meaning of constitutional provisions should interpret them in the manner that provides the almost benefit, and that legislatures' existence able to restrict gubernatorial appointment potency provides a substantial do good to the states.[64]

Reform and repeal efforts [edit]

Notwithstanding controversies over the effects of the Seventeenth Subpoena, advocates have emerged to reform or repeal the amendment. Under President Barack Obama'south administration in 2009, 4 sitting Democratic senators left the Senate for executive branch positions: Barack Obama (President), Joe Biden (Vice President), Hillary Clinton (Secretary of State), and Ken Salazar (Secretary of the Interior). Controversies developed about the successor appointments fabricated by Illinois governor Rod Blagojevich and New York governor David Paterson. New interest was aroused in abolishing the provision for the Senate appointment past the governor.[65] Appropriately, Senator Russ Feingold of Wisconsin[66] and Representative David Dreier of California proposed an amendment to remove this ability; senators John McCain and Dick Durbin became co-sponsors, every bit did Representative John Conyers.[65]

Some members of the Tea Political party motility argued for repealing the Seventeenth Amendment entirely, claiming it would protect states' rights and reduce the power of the federal government.[67] On March 2, 2016, the Utah legislature canonical Senate Articulation Resolution No.2 request Congress to offering an amendment to the United States Constitution that would repeal the Seventeenth Amendment.[68] As of 2010[update], no other states had supported such an subpoena, and some politicians who had made statements in favor of repealing the subpoena had afterward reversed their position on this.[67]

On July 28, 2017, after senators John McCain, Susan Collins and Lisa Murkowski voted no on Affordable Care Human activity repeal attempt Wellness Intendance Liberty Human activity, onetime Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee endorsed the repeal on the Seventeenth Amendment, claiming that senators chosen past state legislatures will work for their states and respect the Tenth Amendment,[69] and also that straight election of senators is a major cause of the "swamp".[70]

In September 2020, Senator Ben Sasse of Nebraska endorsed the repeal of the Seventeenth Subpoena in a Wall Street Journal stance piece.[71]

References [edit]

- ^ "BACON, Augustus Octavius (1839–1914)". Biographical Directory of the U.S. Congress. Archived from the original on February 24, 2020. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

became the first U.S. Senator elected by popular vote following ratification of the 17th Subpoena, on July xv, 1913

- ^ "The Constitution of the United states Amendments 11–27". National Archives and Records Assistants. Archived from the original on May 26, 2013. Retrieved January vii, 2011.

- ^ Zywicki (1997) p. 169

- ^ Vile (2003) p. 404

- ^ Zywicki (1994) p. 1013

- ^ Riker (1955) p. 452

- ^ Bybee 1997, p. 516.

- ^ Bybee 1997, p. 515.

- ^ Zywicki (1994) p. 1019

- ^ Zywicki (1997) p. 176

- ^ Zywicki (1997) p. 180

- ^ a b Bybee (1997) p. 538

- ^ Bybee 1997, p. 539.

- ^ a b Zywicki (1994) p. 1022

- ^ Bybee 1997, p. 541.

- ^ "Direct Election of Senators". United States Senate. Archived from the original on December six, 2017. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- ^ Schiller et al. (July 2013) p. 836

- ^ An Human activity to regulate the Times and Manner of holding Elections for Senators in Congress, July 25, 1866, ch. 245, xiv Stat. 243.

- ^ Schiller et al. (July 2013) pp. 836–37

- ^ a b Bybee (1997) p. 542

- ^ Zywicki (1994) p. 1024

- ^ Ure (2007) p. 286

- ^ Bybee 1997, p. 543.

- ^ a b c Schleicher, David (February 27, 2014). "States' Wrongs". Slate. Archived from the original on October fifteen, 2014. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ Stathis, Stephen W. (2009). Landmark debates in Congress: from the Declaration of independence to the state of war in Republic of iraq. CQ Press. p. 253. ISBN978-0-87289-976-6. OCLC 232129877.

- ^ a b Bybee 1997, p. 536.

- ^ Boyer, Paul S.; Dubofsky, Melvyn (2001). The Oxford companion to United States history . Oxford University Press. p. 612. ISBN978-0-19-508209-8. OCLC 185508759.

- ^ "Direct Ballot of Senators" Archived December vi, 2017, at the Wayback Car, U.s. Senate webpage, Origins and Development—Institutional.

- ^ a b c Bybee (1997) p. 537

- ^ MacNeil, Neil and Richard A. Bakery, The American Senate: An Insider's History 2013, ISBN 978-0-19-536761-4. pp. 22–23.

- ^ Bybee 1997, p. 544.

- ^ Bybee 1997, p. 545.

- ^ Bybee 1997, p. 546.

- ^ MacNeil, Neil and Richard A. Baker, The American Senate: An Insider'south History 2013, ISBN 978-0-19-536761-4. p. 23.

- ^ Rossum (1999) p. 708

- ^ Rossum (1999) p. 710

- ^ "17th Subpoena: Direct Ballot of U.S. Senators". August 15, 2016. Archived from the original on Apr iv, 2017. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ Zachary Clopton & Steven E. Art, "The Meaning of the Seventeenth Amendment and a Century of State Defiance" Archived April 4, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, 107 Northwestern University Law Review 1181 (2013), pp. 1191–1192

- ^ "17th Subpoena to the U.S. Constitution: Straight Election of U.S. Senators". Baronial 15, 2016. Archived from the original on April 28, 2017. Retrieved Apr 3, 2017.

- ^ a b James J. Kilpatrick, ed. (1961). The Constitution of the United States and Amendments Thereto. Virginia Commission on Constitutional Government. p. 49.

- ^ POM-309 Archived Jan xv, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, House Articulation Resolution No. 12, A articulation resolution adopted by the Legislature of the State of Alabama relative to ratifying the Seventeenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, Volume 148 Congressional Record page 18241 (permanent, bound edition) and page S9419 (preliminary, soft-cover edition). September 26, 2002. Retrieved May ten, 2012.[ chronology citation needed ]

- ^ "Formally Ratifying the 17th Amendment to the Constitution of the U.s.a. Providing for the Pop Ballot of Senators to the U.s. Senate". State of Delaware. Archived from the original on Feb 10, 2015. Retrieved February nine, 2015.

- ^ Senate Joint Resolution 2, Apr 1, 2012, archived from the original on December xiv, 2013, retrieved Apr 29, 2012

- ^ House Joint Resolution 3, Apr 1, 2012, archived from the original on December 14, 2013, retrieved April 29, 2012

- ^ Bills signing May 22, 2012 (PDF), May 22, 2012, archived from the original (PDF) on January fifteen, 2013, retrieved May 23, 2012

- ^ At the time, Article XVI, Section nineteen, of the Florida Constitution provided that "No Convention nor Legislature of this State shall deed upon whatever amendment of the Constitution of the United states proposed by Congress to the several States, unless such Convention or Legislature shall take been elected later such amendment is submitted." The offset legislature elected afterward such submission did not encounter until Apr 5, 1913. See Fla. Const. of 1885, Art. III, § 2. By that time, the subpoena had been ratified by 35 states, and, every bit noted in a higher place, would be ratified past the 36th state on Apr 8, 1913, a circumstance which made any action past the Florida Legislature unnecessary.

- ^ Bybee 1997, p. 552.

- ^ Bybee 1997, p. 552. Similarly, he believes the Republican Revolution of 1994 would non have happened; instead, the Democrats would have controlled 70 seats in the Senate to the Republicans' 30. See Bybee 1997, p. 553

- ^ Bybee 1997, p. 535. This was partially fueled by the senators; he wrote in the Northwestern University Law Review:

See Bybee 1997, p. 536.Politics, like nature, abhorred a vacuum, so senators felt the pressure to do something, namely enact laws. Once senators were no longer answerable to and constrained by state legislatures, the maximizing function for senators was unrestrained; senators almost always constitute in their ain interest to procure federal legislation, even to the detriment of state control of traditional state functions.

- ^ Rossum (1999) p. 715

- ^ Ure (2007) p. 288

- ^ Kochan (2003) p. 1053 Donald J. Kochan, for an commodity in the Albany Law Review, analyzed the effect of the Seventeenth Subpoena on Supreme Courtroom decisions over the constitutionality of country legislation. He found a "statistically meaning difference" in the number of cases property state legislation unconstitutional before and subsequently the passage of the Seventeenth Amendment, with the number of holdings of unconstitutionality increasing sixfold. Likewise the Seventeenth Amendment, turn down in the influence of u.s. likewise followed economic changes. Zywicki observes that interest groups of all kinds began to focus efforts on the federal authorities, as national problems could not exist directed past influencing merely a few state legislatures of with senators of the most seniority chairing the major committees. He attributes the rising in the strength of involvement groups partially to the development of the U.S. economy on an interstate, national level. Run across Zywicki (1997) p. 215. Ure besides argues that the Seventeenth Amendment led to the ascent of special interest groups to fill the void; with citizens replacing state legislators as the Senate's electorate, with citizens being less able to monitor the actions of their senators, the Senate became more than susceptible to pressure from involvement groups, who in turn were more than influential due to the centralization of power in the federal government; an interest group no longer needed to lobby many state legislatures, and could instead focus its efforts on the federal government. Run across Ure (2007) p. 293

- ^ Berke, Richard Fifty. (Feb 17, 2002). "Coin Talks; Don't Discount the Fat Cats". The New York Times . Retrieved February xiii, 2021.

- ^ Vile (2010) p. 197

- ^ Neale, Thomas H. (Apr 12, 2018). "U.S. Senate Vacancies: Contemporary Developments and Perspectives" (PDF). fas.org. Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on June v, 2018. Retrieved Oct 13, 2018.

- ^ a b c Dubin, Michael J. (1998). United States Congressional elections, 1788–1997: the official results of the elections of the 1st through 105th Congresses. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN0-7864-0283-0.

- ^ "Voice communication to the People of Washington by Senator Jonathan Bourne Jr. of Oregon, n.d." U.S. Capitol Company Center . Retrieved March 22, 2022.

- ^ Trinsey v. Pennsylvania , 941 (F.2d 1991).

- ^ Aureate (1992) p. 202

- ^ Novakovic (1992) p. 940

- ^ Novakovic (1992) p. 945

- ^ Amar (2008) p. 728

- ^ Amar (2008) pp. 729–30

- ^ Levinson (2008) pp. 718–9

- ^ a b Hulse, Carl (March 10, 2009). "New Idea on Capitol Hill: To Bring together Senate, Get Votes". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August thirty, 2011. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- ^ Southward.J.Res.7—A articulation resolution proposing an amendment to the Constitution of the United States relative to the ballot of Senators., August six, 2009, archived from the original on June xv, 2014, retrieved June 15, 2014

- ^ a b Firestone, David (May 31, 2010). "So You Still Desire to Choose Your Senator?". New York Times. Archived from the original on Jan thirteen, 2012. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- ^ "SJR002". State of Utah. Archived from the original on March 29, 2016. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ "Gov. Mike Huckabee on Twitter: "Time to repeal 17th Amendment. Founders had it right-Senators chosen by state legislatures. Will piece of work for their states and respect 10th amid"". Archived from the original on Oct four, 2020. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ "Archived re-create". Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy equally title (link) - ^ "Ben Sasse Calls for Repealing 17th Subpoena, Eliminating Popular-Vote Senate Elections". National Review. September 9, 2020. Archived from the original on September 28, 2020. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

Bibliography [edit]

- Amar, Vikram David (2008). "Are Statutes Constraining Gubernatorial Power to Make Temporary Appointments to the U.s. Senate Constitutional Under the Seventeenth Amendment?". Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly. University of California, Hastings College of the Police. 35 (4). ISSN 0094-5617. SSRN 1103590.

- Bybee, Jay S. (1997). "Ulysses at the Mast: Democracy, Federalism, and the Sirens' Song of the Seventeenth Amendment". Northwestern University Law Review. Northwestern University School of Constabulary. 91 (1). ISSN 0029-3571.

- Gold, Kevin Thousand. (1992). "Trinsey five. Pennsylvania: State Discretion to Regulate Us Senate Vacancy". Widener Journal of Law and Public Policy. Widener University School of Law. ii (i). ISSN 1064-5012.

- Haynes, George Henry (1912). Ringwalt, Ralph Curtis (ed.). The Election of Senators. H. Holt.

- Hoebeke, Christopher Hyde (1995). The route to mass democracy: original intent and the Seventeenth Subpoena. Transaction Publishers. ISBNane-56000-217-four.

- Kochan, Donald J. (2003). "Country Laws and the Independent Judiciary: An Analysis of the Effects of the Seventeenth Amendment on the Number of Supreme Court Cases Holding State Laws Unconstitutional". Albany Police Review. 66 (1). ISSN 0002-4678. SSRN 907518.

- Levinson, Sanford (2008). "Political Party and Senatorial Succession: A Response to Vikram Amar on How Best to Interpret the Seventeenth Amendment". Hastings Ramble Police Quarterly. University of California, Hastings Higher of the Law. 35 (4). ISSN 0094-5617.

- Novakovic, Michael B. (1992). "Constitutional Law: Filling Senate Vacancies". Villanova Constabulary Review. Villanova University School of Law. 37 (1). ISSN 0042-6229.

- Riker, William H. (1955). "The Senate and American Federalism". American Political Science Review. American Political Science Association. 49 (2): 452–469. doi:10.2307/1951814. ISSN 0003-0554. JSTOR 1951814. S2CID 144680174.

- Rossum, Ralph A. (1999). "The Irony of Constitutional Democracy: Federalism, the Supreme Court, and the Seventeenth Amendment". San Diego Law Review. University of San Diego Schoolhouse of Law. 36 (iii). ISSN 0886-3210.

- Tushnet, Mark (2010). The Constitution of the Usa of America: A Contextual Analysis. Hart Publishing. ISBN978-1-84113-738-4.

- Ure, James Christian (2007). "You Scratch My Back and I'll Scratch Yours: Why the Federal Matrimony Amendment Should Also Repeal the Seventeenth Subpoena". South Texas Constabulary Review. Southward Texas College of Law. 49 (1). ISSN 1052-343X.

- Vile, John R. (2003). Encyclopedia of constitutional amendments, proposed amendments, and alteration problems, 1789–2002 (2nd ed.). ABC-CLIO. ISBN978-1-85109-428-8.

- Vile, John R. (2010). A companion to the U.s. Constitution and its amendments (5th ed.). ABC-CLIO. ISBN978-0-313-38008-2.

- Zywicki, Todd J. (1994). "Senators and Special Interests: A Public Choice Assay of the Seventeenth Subpoena" (PDF). Oregon Constabulary Review. University of Oregon Schoolhouse of Law. 73 (1). ISSN 0196-2043.

- Zywicki, Todd J. (1997). "Beyond the Crush and Husk of History: The History of the Seventeenth Subpoena and its Implications for Current Reform Proposals" (PDF). Cleveland Country Constabulary Review. Cleveland-Marshall Higher of Law. 45 (ane). ISSN 0009-8876.

- Wendy J. Schiller and Charles Stewart Three (May 2013), The 100th Ceremony of the 17th Subpoena: A Promise Unfulfilled?, Issues in Governance Studies, Number 59 May 2013

- Schiller, Wendy J.; Stewart, Charles; Xiong, Benjamin (July 2013). "U.S. Senate Elections earlier the 17th Subpoena: Political Political party Cohesion and Disharmonize 1871–1913". The Journal of Politics. 75 (3): 835–847. doi:x.1017/S0022381613000479.

External links [edit]

![]()

Was The 17th Amendment Successful,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seventeenth_Amendment_to_the_United_States_Constitution

Posted by: oconnellsilth1993.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Was The 17th Amendment Successful"

Post a Comment